One of the more peculiar passages in a Shakespeare play is found in Act V, Scene 1 of As You Like It, when the clown Touchstone encounters a naïve rustic named William. The scene has been analyzed by commentators of all stripes, but like many others, I find it particularly interesting when viewed from an anti-Stratfordian perspective. (A thorough analysis by an Oxfordian is found here.)

Earlier in the play, we’ve seen that Touchstone lusts after a country wench named Audrey. Because she is unwilling to surrender her virginity outside of wedlock, he has decided he must marry her. He makes an abortive attempt to tie the knot in Act III, Scene 3, but is temporarily talked out of it. When we see him again in Act V, he is still intent on marriage, but there is a minor obstacle in his way. A local boy, William, also has designs on the maid.

This sets up Touchstone’s encounter with William, whom he proceeds to humiliate in a show of intellectual superiority. Though the entire relationship between Touchstone and Audrey is of interest, it is this dialogue exchange in particular that has excited the most critical discussion.

TOUCHSTONE How old are you, friend?

WILLIAM Five-and-twenty, sir.

TOUCHSTONE A ripe age. Is thy name William?

WILLIAM William, sir.

TOUCHSTONE A fair name. Wast born i’ th’ forest here?

WILLIAM Ay, sir, I thank God.

TOUCHSTONE “Thank God.” A good answer. Art rich?

WILLIAM ’Faith sir, so-so.

TOUCHSTONE “So-so” is good, very good, very excellent

good. And yet it is not: it is but so-so. Art thou wise?WILLIAM Ay, sir, I have a pretty wit.

TOUCHSTONE Why, thou sayst well. I do now remember

a saying: “The fool doth think he is wise, but the

wise man knows himself to be a fool.”

So William is a good-natured country lad who grew up in the forest of Arden – which, while obviously referring to Ardennes in France, may also be taken as a reference to the Forrest of Arden in Warwickshire, home of Stratford-upon-Avon. He sees himself as having a quick wit, but Touchstone demurs, regarding him as a fool. It should be noted that the dictionary definition (Oxford Languages) of touchstone is:

a piece of fine-grained dark schist or jasper formerly used for testing alloys of gold by observing the color of the mark which they made on it;

a standard or criterion by which something is judged or recognized.

In this case, Touchstone has tested William and found that he is only fool’s gold.

TOUCHSTONE You do love this maid?

WILLIAM I do, sir.

TOUCHSTONE Give me your hand. Art thou learned?

WILLIAM No, sir.

TOUCHSTONE Then learn this of me: to have is to have.

For it is a figure in rhetoric that drink, being poured

out of a cup into a glass, by filling the one doth

empty the other. For all your writers do consent

that ipse is “he.” Now, you are not ipse, for I am he.

The Latin word ipse means he himself or the man himself. Touchstone’s metaphor, following immediately upon William’s admission that he is unlearned, suggests that whatever learning or wit William seems to possess has been poured into him, filling him up while emptying another. “You are not the man himself,” Touchstone says in effect; “I am he.”

WILLIAM Which he, sir?

TOUCHSTONE He, sir, that must marry this woman.

Touchstone then abuses William with threats and insults until William, intimidated, departs. All this for love of Audrey, whom Touchstone is eventually set to marry.

What can we make of this? It must have been put in for a reason, but not to advance the plot, which it doesn’t. None of it is found in the 1590 novel Rosalynde; or, Euphues' Golden Legacy, by Thomas Lodge, which was either the source of the play or a later adaptation of it. The entire business can be excised without altering the main story.

And it’s very odd. There’s no particular reason for Touchstone to be enamored of Audrey, who describes herself as unattractive and who has virtually no lines and no personality. There also seems to be no reason to bring in William at all, to confuse him with a rather opaque metaphor, or to threaten him with punishment and death.

Anti-Stratfordians, like me, see this entire subplot as a thinly veiled commentary on the relationship between the author of the play – call him the Bard – and William Shakespeare of Stratford, who had acquired the rights to his works and was taking the credit. In this interpretation, Touchstone stands for the Bard, William stands for the Stratford man, and Audrey stands either for the literary works the Bard has authored or perhaps for the audience that has enjoyed and acclaimed those works. (The name “Audrey” shares the sound aud in common with auditory and audience, though there is no actual etymological connection.)

In this reading, the Bard wishes to attain formal union with his works or formal recognition from his audience. Either way, William stands as an impediment. The Bard, frustrated, tells William that he is an empty vessel who has only been filled up by the Bard’s own talent, emptying the Bard in the process. William, he says, is not the man himself — because he, the Bard, is the man. “You are not ipse, for I am he.” Finally, having gotten himself worked up, he lashes out with angry threats until the terrified yokel runs away.

Having dispatched the pretender, the Bard is free to be openly united with his works and/or his audience — a fairy-tale ending for the true author. It couldn’t happen in real life, but … he could dream, couldn’t he?

Speculation? Sure. But the overall relationship of Touchstone, Audrey, and William, is difficult to explain otherwise. We might, of course, say merely that the playwright was writing nonsense and meant nothing in particular by any of it, and that could be true.

But if this strange pastoral interlude means anything at all, it probably means that the Bard was feeling frustrated with Will, and worked out his feelings as writers do — in a web of carefully chosen words.

P.S. An authorship clue?

Who is the Bard? There may be a hint in the text.

At the end of the play, the god of marriage addresses Touchstone and Audrey, assessing their compatibility:

You and you are sure together

As the winter to foul weather.

In his dialogues with Audrey, Touchstone has characterized her more than once as “foul,” a description she herself has accepted. If, then, “foul weather” relates to Audrey, “winter” must refer to Touchstone.

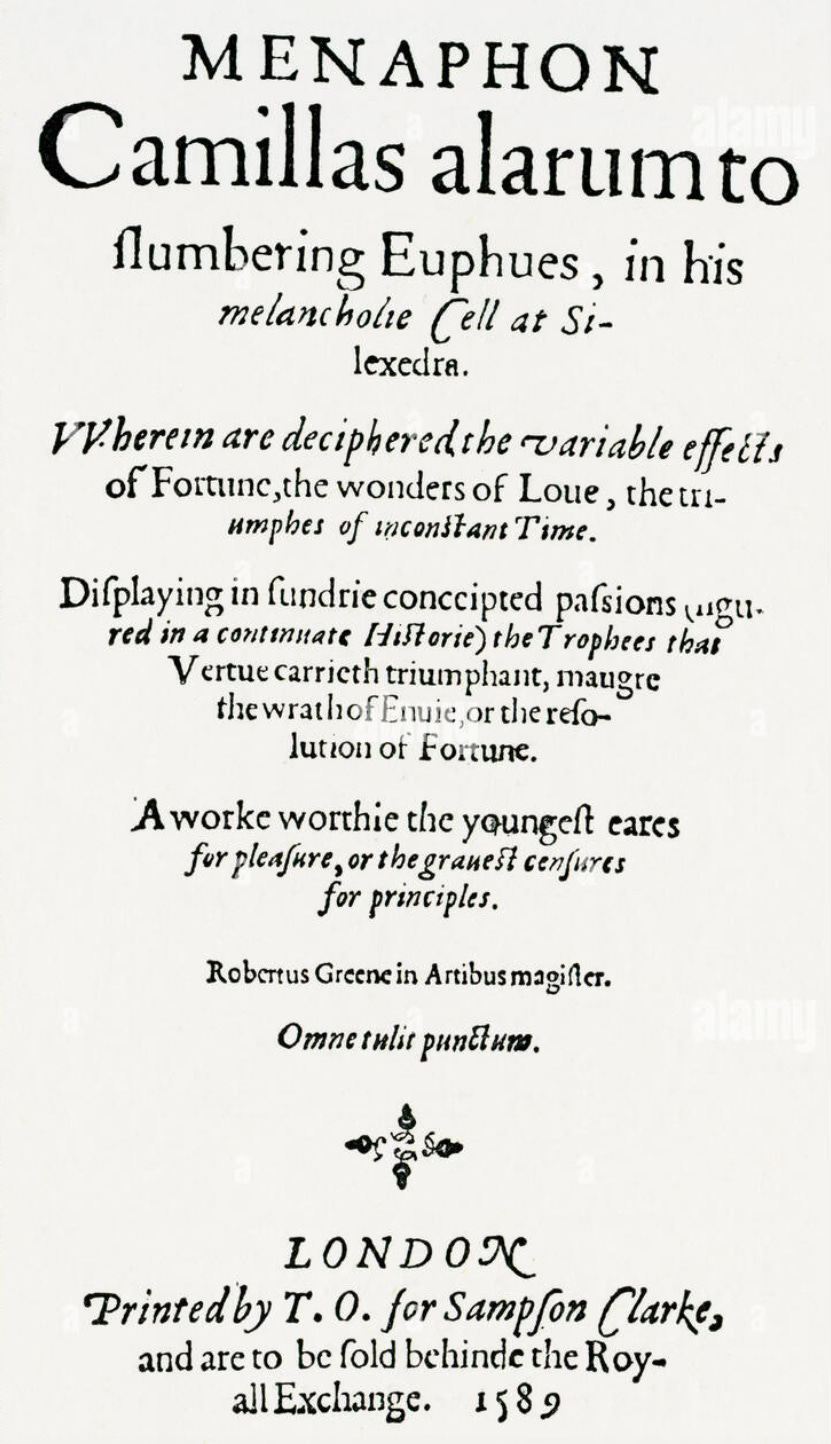

Now bear with me. In his preface to Robert Greene’s Menaphon (1589), the satirist Thomas Nashe attacks playwrights of the period. He says mockingly that he means to

talk a little in friendship with a few of our trivial translators. It is a common practice now-a-days amongst a sort of shifting companions, that run through every art and thrive by none, to leave the trade of noverint whereto they were born and busy themselves with the endeavours of art, that could scarcely Latinize their neck-verse if they should have need; yet English Seneca read by candlelight yields many good sentences, as Blood is a beggar, and so forth, and if you entreat him fair in a frosty morning, he will afford you whole Hamlets, I should say handfuls, of tragical speeches. (bold emphases added)

This last is taken as a reference to an early, lost version of Hamlet. Nashe can be hard to decipher, but the gist seems to be that nowadays any restless law-clerk (noverint) can turn his meager learning to the writing of plays, and some of these “trivial translators,” imitating the classics, actually do produce memorable lines and “tragical speeches.” Moreover, if you ask a certain “English Seneca” to recite some lines “on a frosty morning,” he’ll recite his whole Hamlet.

Now, Thomas North was trained in the law and became a translator, best known for his 1580 publication of Plutarch’s Lives, a classical work. Textual evidence strongly suggests that he wrote the originals of Shakespeare’s plays, including Hamlet.

But why should we entreat him on a “frosty” morning? For that matter, why does Nashe earlier chastise

vainglorious tragedians, who contend not so seriously to excel in action as to embowel the clouds in a speech of comparison, thinking themselves more than initiated in poets' immortality if they but once get Boreas by the beard and the heavenly bull by the dewlap. (bold emphasis added)

The tragedians are actors, and their recent stage antics remind Nashe of the effrontery of grabbing Boreas, the god of the frigid north wind, by the beard.

Nashe’s associative style is subtle, sometimes to the point of obscurity. Do we find here an ongoing association between a frosty morning, the cold north wind, and a tragical play by an English translator steeped in the classics? Cold-winter-North? Maybe. And could this be why Touchstone is “the winter” to Audrey’s “foul weather”? Again … maybe.

Admittedly, this is the kind of stray detail you can pick up to support many different hypotheses. I wouldn’t make too much of it. It’s just a notion that you can take or leave … as you like it.

Excellent article, thank you.