Disneyland-on-Avon

Alden Brooks’ Will Shakspere: Factotum and Agent (Round Table Books, 1937) begins with an amusing discussion of “the Birthplace,” otherwise known as Shakespeare’s purported home in Stratford-on-Avon.

Brooks quotes from an influential 1815 essay by Washington Irving, recounting his visit to the holy site:

The house is shown by a garrulous old lady, in a frosty red face, lighted up by a cold blue anxious eye, and garnished with artificial locks of flaxen hair, curling from under an exceedingly dirty cap. She was peculiarly assiduous in exhibiting the relics with which this, like all other celebrated shrines, abounds. There was the shattered stock of the very matchlock with which Shakespeare shot the deer on his poaching exploits. There, too, was his tobacco-box – which proves that he was a rival smoker of Sir Walter Ralegh; the sword also with which he played Hamlet; and the identical lantern with which Friar Laurence discovered Romeo and Juliet at the tomb! There was an ample supply also of Shakespeare’s mulberry-tree, which seems to have as extraordinary powers of self-multiplication as the wood of the true cross, of which there is enough extant to build a ship of the line.

The most favorite object of curiosity, however, is Shakespeare’s chair. It stands in the chimney nook of a small gloomy chamber, just behind what was his father’s shop. In this chair it is the custom of everyone that visits the house to sit. Whether this be done with the hope of imbibing any of the inspiration of the bard, I am at a loss to say; I merely mention the fact: and mine hostess privately assured me that though built of solid oak, such was the fervent zeal of devotees, that the chair had to be new bottomed at least once in three years. It is worthy of notice, also, in the history of this extraordinary chair, that it partakes something of the volatile nature of the Santa Causa of Lorette, or the flying chair of the Arabian princess; for though sold some few years since to a northern princess, yet, strange to tell, it has found its way back to the old chimney-corner.

The image of the chair being hollowed out every few years by the friction of countless reverent bottoms is amusing. So is the comparison to the Santa Causa, a Catholic shrine to which the house of the Virgin Mary is said to have been miraculously transported. The chair, by the way, really was sold to a Russian princess for twenty guineas, but magically returned to Stratford to inspire new generations of arses.

Brooks goes on to recount his own visit to Stratford around the time of writing – that is, the 1930s. He notes that the marvelous chair still occupied its appointed place. Moreover:

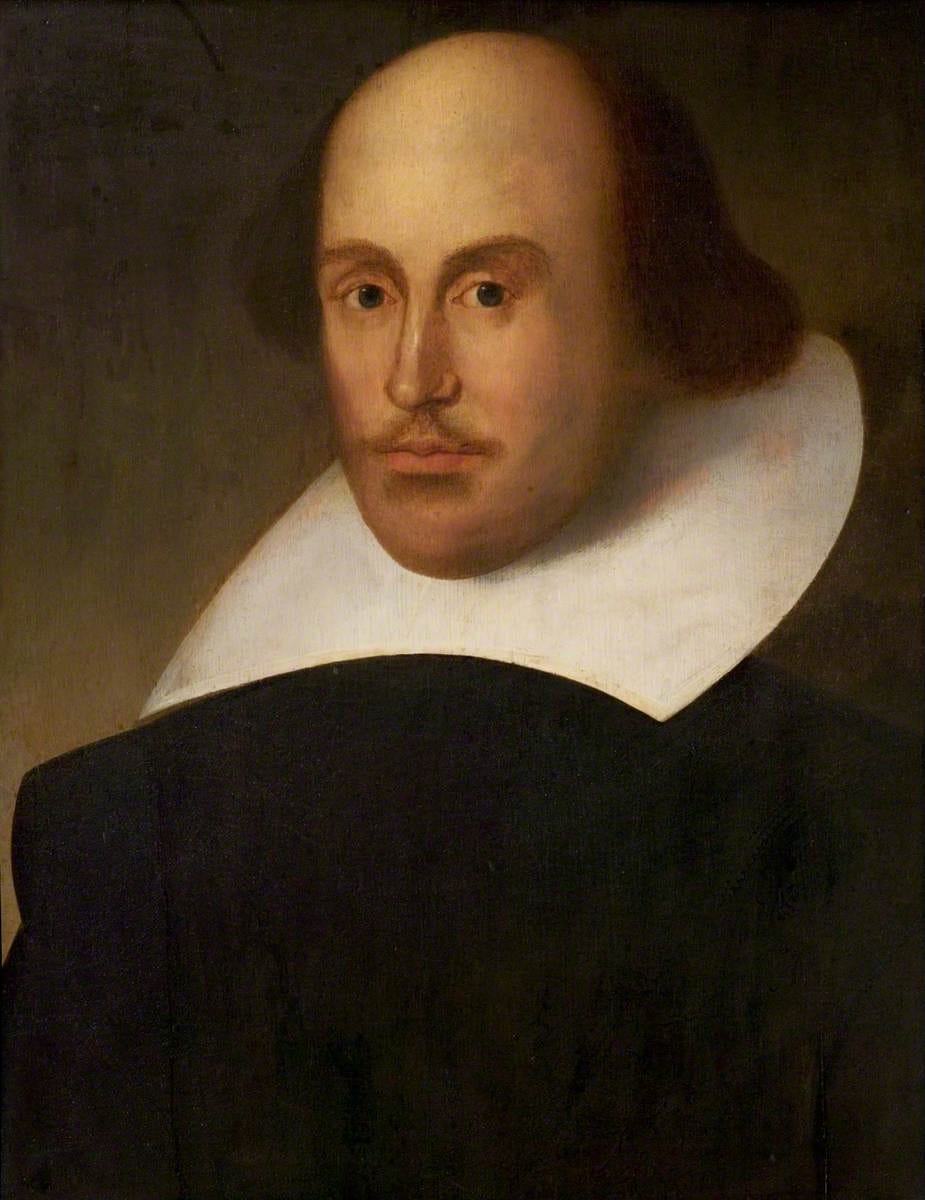

On the wall hangs the “Ely Palace” portrait of Shakespeare, [a] painting that has been declared spurious by every expert. The poet’s golden signet ring came to light first in 1810, and even so was brought forward without evidence that it belonged to Shakespeare, and in a brightly polished condition, and ready for sale. As for “Shakespeare’s school-desk,” though a brass plate in the ancient grammar-school marks the very spot, at the head of the class, where the desk once stood, no school list or recorded word lives to indicate that Shakespeare even went to the school. And in any case, the school-room of those sixteenth century days was situated elsewhere – in a portion of the “Court” afterwards converted into a dwelling-Place by Alexander Aspinall.…

Throughout the length and breadth of Stratford the spurious reigns. And yet it is in this corrupt atmosphere that the story of Shakespeare’s life invariably begins and develops. “Ay, now I am in Arden,” reverberates from mementos everywhere, as if the words were repeated echoes of joyful emotion from the lips of the author of As You Like It at being again in Stratford. Touchstone’s words, however, do not carry this suggestion. Touchstone, clown at the court of the French duke, is referring to the Forest of Ardennes France, and not to the Forest of Arden, Warwickshire, and his completed remark runs, “Ay, now I am in Arden. The more fool I; when I was at home, I was in a better place, but travellers must be content.”