Fish Story

I did a lot of research over the past several months for a forthcoming historical fantasy novel set in ancient Nineveh, the capital city of the Assyrian Empire. In doing so, I came across an interesting perspective on the Biblical story of Jonah.

Because so many centuries have passed, the writings of the Bible have taken on a sheen of holiness, and any suggestion that some might have been intended as less than serious is regarded as disrespectful, if not downright blasphemous. And yet ancient people did have a sense of humor, and it would be odd if some of their writings didn’t reflect it. I think Jonah is one of those writings. Basically it’s a parody of an established genre of that era – the genre of the appointed prophet of God.

Genres have rules, and when people become overly familiar with those rules, they can’t help starting to twist them in new ways, eventually making them ridiculous. The early Universal horror movies took themselves more or less seriously, but Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Wolfman ended up as fodder for Abbott and Costello. Film noir was a dark, disturbing genre in its day, but ultimately it was the target of send-ups like Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid and The Cheap Detective.

The prophet genre had its own rules, a standard formula. The story begins when God, for inscrutable reasons, selects a seemingly ordinary fellow to prophesy for him. The selectee is understandably reluctant, but piously agrees to do his best. His mission, typically, is to preach to his fellow Hebrews, telling them that they are guilty of backsliding and will face divine punishment unless they shape up. Diligently he pursues this task for years on end, but his neighbors ignore him, until finally God’s patience is exhausted and he brings down punishment on their heads, usually in the form of an invading army.

Now if we look at the Book of Jonah, we can see that every one of these story points is turned on its head.

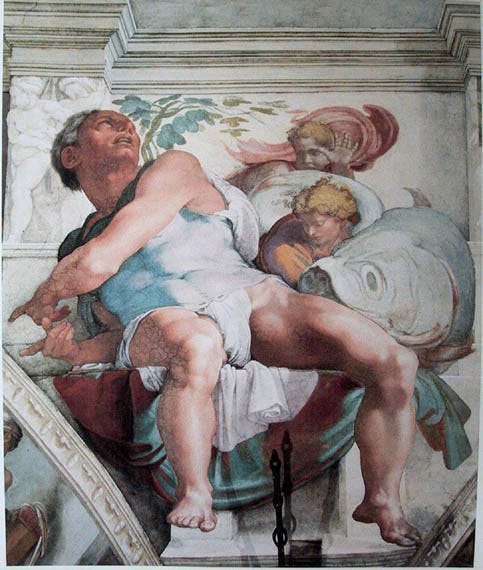

When God nominates Jonah, the poor fellow is not merely reluctant to go along with the plan; he is completely unwilling. In fact, his response is to run to the nearest harbor and jump on the first ship that’s leaving. Apparently he intends to outrun God, a ridiculous enough idea. But we can understand his reaction, because God’s plan is kind of crazy. He doesn’t want Jonah to preach to the Hebrews, who might possibly be receptive to his message; no, he says Jonah must go to Nineveh, the mightiest city in the world, heart of a pagan empire, and preach to the populace there. This would be like appointing some random guy to preach the virtues of capitalism in the middle of Red Square circa 1965. It is a plan with no prospect of success. Moreover, Assyria was known as not only the most powerful empire of its day, but also the cruelest. The Assyrians disposed of their enemies by flaying them alive or by impaling them through the rectum. No wonder poor Jonah ran away.

But of course his escape attempt is futile. The ship is beset by a terrible storm, and the sailors (correctly) divine that Jonah is the jinx and toss him overboard. As we all know, he doesn’t drown, but is instead swallowed by a “great fish.” Incidentally, the text does not say anything about a whale. The ancient Hebrews’ knowledge of marine fauna was pretty sketchy, and it is entirely likely that what they visualized was not a whale, but an ordinary- looking fish roughly the size of a Greyhound bus.

Jonah, of course, does not die, as anybody else would, but camps out in the fish’s belly for three days while the fish swims to the nearest shore, following God’s instructions. (“The Lord spake onto the fish.”) There he is unceremoniously barfed up the beach.

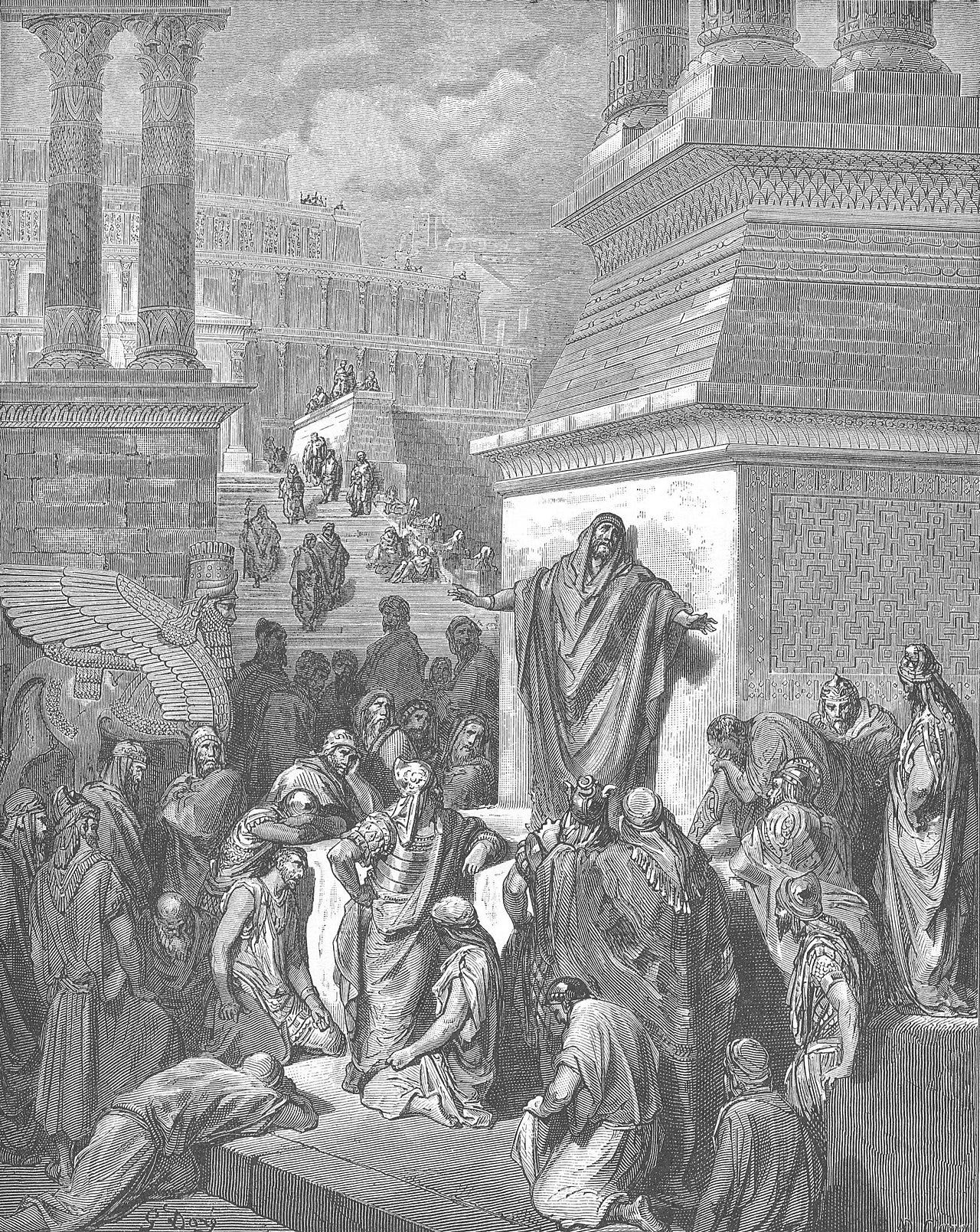

Resigned to his fate, Jonah makes his way to Nineveh – undoubtedly a long trek, since Nineveh (modern-day Mosul in Iraq) is nowhere near the ocean. The city is described as so huge that it takes three days to cross it; it boasts a population of more than 120,000. This is a wild exaggeration; though Nineveh was large by the standards of its time, it covered only about three miles from the south gate to the north, and it could not have supported a population of that size. But given that we’ve already heard about a fish big enough to swallow a man whole, this new embellishment doesn’t seem too unreasonable.

Jonah begins to preach. Realistically he cannot expect to gain any followers. There is no reason why Nineveh, proud capital of an empire that has swallowed up or subjugated most surrounding nations, would have the least interest in the rantings of an Israelite about the deity foreign to their own pantheon. The likeliest outcome is that he will end up skewered on a spit in a public square.

But what happens? In just one day, Jonah converts the entire population to Judaism!

Not only are the common folks persuaded, but the king himself and all his nobles jump on the bandwagon. Where all other Hebrew prophets failed even to stiffen the spines of their own people, Jonah – who doesn’t even want to be a prophet – manages to overturn Assyria’s most venerated religious traditions, at the highest level, in no time at all.

Now, if Nineveh and the king had in fact adopted Judaism, the Assyrian Empire as a whole would have done likewise. Needless to say, nothing like this ever happened; and also needless to say, the audience who listened to the story knew perfectly well that nothing like this had ever happened. They knew that neither Assyria nor any other world empire had been converted to their religion.

Jonah, one assumes, would be pleased by the successful – and remarkably easy – fulfillment of his mission. No. “But it displeased Jonah exceedingly, and he was very angry.” Apparently he didn’t want the Ninevens to be saved, because he feels, rather churlishly, that salvation should be reserved for the Hebrews.

The story ends with a still-dissatisfied Jonah living as a hermit in a booth outside the city and complaining about the most trivial things. Despite being the most successful prophet in history, he remains ticked off about having been chosen in the first place. And God is clearly getting tired of him, which is perfectly understandable.

I don’t want to give the impression that every aspect of the story is meant as parody. All Bible stories probably began as oral traditions and went through many revisions before they were written down. In the process, different points of view were appended to the original story, changing the first author’s intentions. For instance, the original version of the story of Job (inspired, it is thought, by Babylonian lamentation poems) probably ended on a despairing note, while a more uplifting ending was provided by another storyteller intent on justifying God’s rather questionable treatment of Job. To take a more obvious example, the Book of Ecclesiastes ends with pious exhortations to trust in God and practice moral virtue, even though most of the book takes a world-weary, highly skeptical attitude toward religion and morality.

In the Jonah story, our hero’s prayer while trapped inside the fish is entirely serious and was probably interpolated by a later storyteller who either missed the humorous dimensions of the tale or disapproved of them. Jonah’s confession to the sailors that he is responsible for the storm seems out of character, and is probably a later insertion intended to make him more admirable.

For other parodic aspects of the story, see this subsection of the Wikipedia article on Jonah.