Pocketful of Miracles — Part Two

In Part One we looked at some pretty bizarre examples of UFO sightings and ET encounters. These cases are a small sample of a much wider variety of anomalous experiences ranging far beyond the UFO phenomenon. Such cases, with their absurdities and illogicality, raise the question of how they can possibly be explained.

The simplest explanation, of course, is that they are simply made up. And I’m sure many are. This includes stories published in the media. A report attributed to “some parties returning from church last night” hardly constitutes firm eyewitness testimony. And 19th century newspapers were even less reliable than the media are today. It was not uncommon for reporters to fabricate tall tales out of thin air.

On the other hand, if a local paper claimed that the entire city was aware of an aerial phenomenon, as in the case of the Omaha, Milwaukee, and Chicago episodes, it seems unlikely that the story was wholly invented.

In any event, the truth or falsehood of these particular cases is not of primary importance. They serve only as examples of the vast and ongoing literature of Forteana. And believe it or not, some cases are even more bizarre than any I’ve cited. In the anthology Deep Weird, contributor Joshua Cutchin casually mentions that while many so-called alien abductees “describe reptilians, insectoids, Space Brothers, and ubiquitous Greys,” there have also been reports of “clowns, pirates, cartoon characters, and manifold other absurd kidnappers. Equally pernicious are reports of beings appearing as drawings come-to-life, or stick figures.” (Chapter 13, “The Projectionist’s Booth.”)

So, for the sake of discussion, let’s posit that the claims listed in Part One (standing in for hundreds of similarly surreal claims) are legitimate. How can we explain them? Three possible approaches occur to me.

Solipsism. We live in a self-created, purely subjective world governed by our subconscious. In such a world, nothing should surprise us.

Collective consciousness. Rather than being alone in our subjective world, we and other minds interact to collectively create a shared environment.

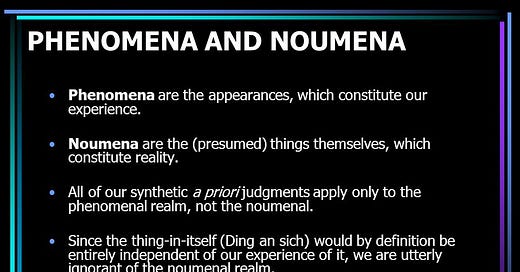

A divided world. There is an underlying reality we cannot perceive directly, as well as a very different, mentally processed version of reality that we take at face value. This is the Kantian distinction between the noumenal and the phenomenal realms. In modern terms, it can be analogized to an underlying reality of pure information (the noumenal realm) and a mentally constructed reality that renders this information into spacetime experience (the phenomenal realm).

If you’ve read my book The Far Horizon, you know I’m partial to the third option. I regard it as an “inference to the best explanation,” inasmuch as it addresses the paradoxes of quantum physics, the existence of Fortean anomalies, and ancient dilemmas like the paradox of Zeno’s arrow.* It is also broadly consistent with Jane Roberts’s channeled “Seth”material, which, despite some inconsistencies, strikes me as among the best literature of its type – good enough that at least one book has been written relating Seth’s theories to quantum physics.

How exactly does the Kantian distinction shed light on Fortean anomalies? I would suggest something like this: The human mind is constructed in such a way as to receive and interpret certain aspects of noumenal reality while remaining blind to others. At times, some of these “noumenal” realities impinge on our consciousness – usually in a fleeting, unpredictable, and confusing manner. Since our mind is not set up to interpret such input, it defaults to familiar categories already on hand.

In the Middle Ages, someone who spotted what we might now call ETs emerging from a UFO (which is itself a mental category) would have interpreted what he saw in terms of his cache of available concepts: leprechauns, fairy folk, angels, devils. In the age of rocketry and spaceflight, the same sighting may be interpreted as the arrival of interplanetary or interstellar travelers. It is unlikely that either interpretation is correct. Each represents a default to the conceptual category most readily available.

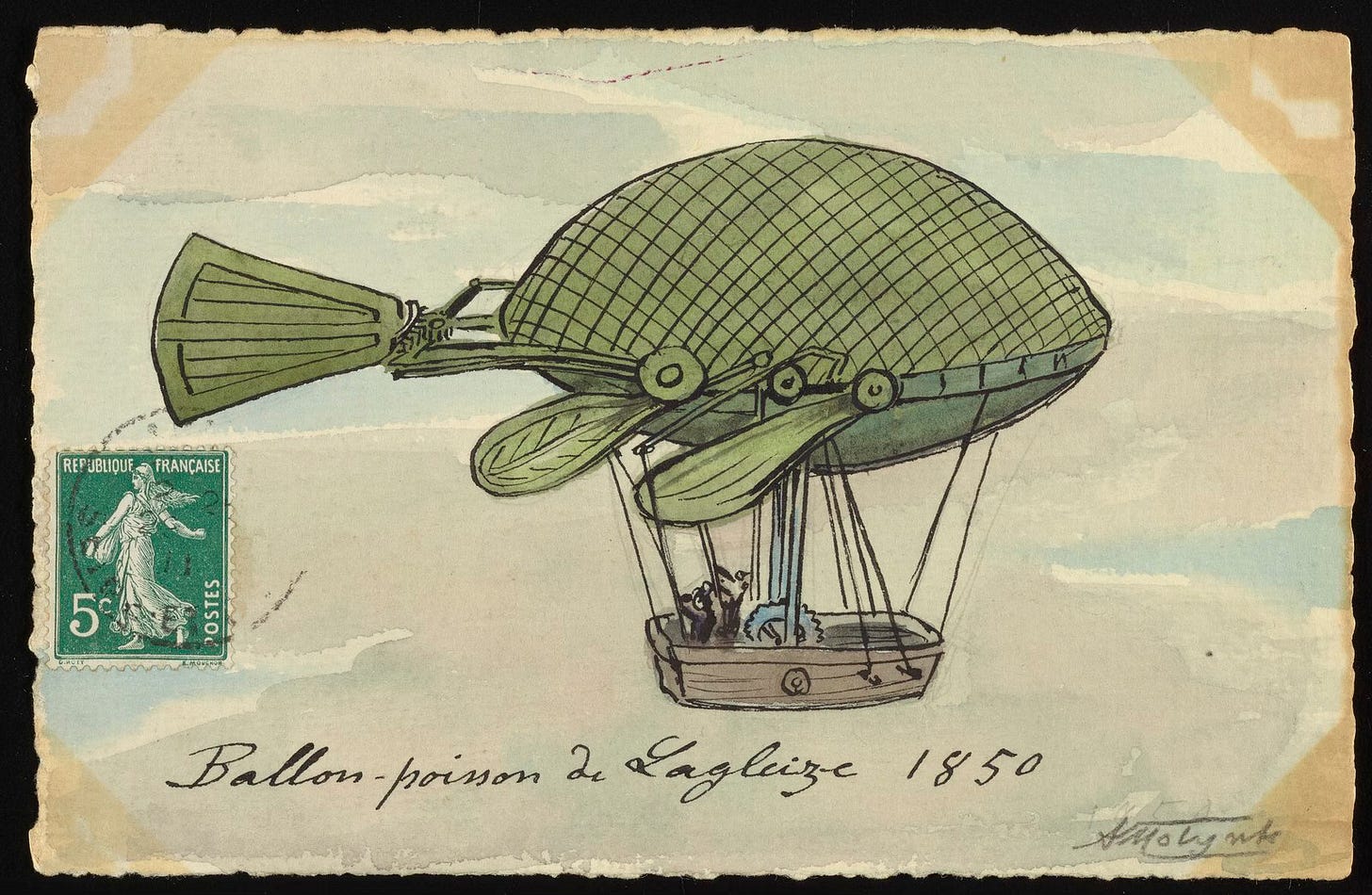

In short, if something that intrudes on our consciousness is outside of any available concepts, the mind slots it into whatever category seems closest, even if the fit is far from perfect. A large hovering image in the sky, which can’t be interpreted in familiar terms, may be interpreted as the next best thing. If speculation about airships has become popular — as, by 1897, it had — then the image will be slotted into the airship category.

An unfathomable sound made by the object may be rendered as orchestral music by our consciousness (as in the Chicago account). An extension from the perceived object may be rendered as an anchor cable. Who knows what it “really” was? A tendril of energy, a robotic arm, a living tentacle? Or something we can’t conceptualize even today?

Why would all observers default to the same associative imagery? Actually, I’m not sure they do. There can be considerable variations in eyewitness accounts. But where the reports do align, maybe the power of suggestion is at play; once one person sees the object as an airship, the people around him fall in line. Or perhaps some form of telepathy allows the imagery to be shared. Or the default image is dictated by a common culture. Or the spurious identification of the unknown entity somehow “fixes” its appearance, much as measuring a a subatomic particle will fix its position for all observers. I don’t know.

The more fundamental point is that the images are part of the mind’s furniture, rather than necessarily being anything external. The iconography employed is dictated by whatever material is available in the storage cache of the subconscious.

In this connection, it’s interesting to take a detour into the subject of Marian apparitions sighted by large crowds, a phenomenon not dissimilar to the mass sightings of airships in 1897. The most famous of these miracles occurred before a crowd of 70,000 people in Fatima, Portugal, on October 13, 1917, and is known as the Miracle of the Sun.

On October 13, 1917, the crowds of witnesses had grown to 70,000 — faithful and skeptics alike gathered for what would be the last Marian apparition to the children in the Cova, eager to see the sign from heaven that Mary had promised …

The rain stopped, the clouds dispersed and the sky cleared, catching the attention of onlookers.

What happened next has been described as the "miracle of the sun" or "the time the sun danced."

"We looked easily at the sun, which did not blind us. It seemed to flicker on and off, first one way and then another. It shot rays in different directions and painted everything in different colors ... What was most extraordinary is that the sun did not hurt our eyes at all. Everything was still and quiet; everyone was looking upwards …" recalled Ti Marto, the father of visionaries Jacinta and Francisco Marto.

O Dia, the newspaper in the Portuguese capital of Lisbon, reported that "at midday by the sun, the rain stopped. The sky, pearly grey in color, illuminated the vast arid landscape with a strange light. The sun had a transparent gauzy veil so that the eye could easily be fixed on it. The grey mother-of-pearl tone turned into a sheet of silver which broke up as the clouds were parted and the silver sun, enveloped in the same gauzy grey light, was seen to whirl and turn in the circle of broken clouds. A cry went up from every mouth and people fell on their knees in the muddy ground…"

Even O Seculo, an anti-Catholic, Masonic newspaper in Lisbon, reported the miracle of the sun from the perspective of the paper's editor-in-chief, Avelino de Almedia, who witnessed the miracle for himself.

"... one could see the immense multitude turn toward the sun, which appeared at its zenith, coming out of the clouds," he wrote.

"Before their dazzled eyes the sun trembled, the sun made unusual and brusque movements, defying all the laws of the cosmos, and according to the typical expression of the peasants, 'the sun danced'."

Less dramatic but still impressive mass sightings include weekly occurrences in Zeitoun, Egypt, between 1968 and 1971, and the apparition of Our Lady of Assiut, also in Egypt, which occurred on multiple occasions between 2000 and 2001. Photos and videos of the more recent events indicate that something happened, though the quality of the images is blurred and open to interpretation.

In one culture, an aerial phenomenon is rendered as an airship; in another, an aerial phenomenon is rendered as the Virgin Mary or a dancing sun. In other cultures, it might be rendered as the goddess Isis, or as a heavenly chariot, or as a supermodern spacecraft.

I use the word “render” because rendering is the term for converting the data and algorithms of a computer program into the icons and animation displayed on a computer screen. In this analogy, consciousness functions as a “render engine,” with each of us rendering our own personal reality, much as each computer terminal in a multiplayer first-person game renders the game’s environment from a particular player’s point of view. But while the point of view varies from screen to screen, the underlying reality – the source code – is the same for all players, thus allowing them to interact in the same environment according to the same rules.

What about purported sightings of – or even interactions with – the occupants of the “airship”? In Merkel, Texas, a supposed crew member was visualized as wearing a blue sailor suit. As before, we should probably interpret this as our subjective rendering system’s “best guess” at the unguessable. Whatever was actually imposing itself on the consciousness of the observers, it surely was not a man in a sailor suit. But if the mind is struggling to interpret utterly unfamiliar input, the logical association of a sailor with a vessel may come to mind.

If any of this is true, then it suggests that the “high strangeness” of many anomalous reports is best understood as a misrendering of profoundly unfamiliar input that cannot be processed accurately. The mind jumps to the best available interpretive model, even if it produces results that are absurd by any common-sense standard.

In Part Three, we’ll take this idea to its logical – albeit unsettling – conclusion.

*Regarding the arrow paradox, here’s something from my old blog:

The idea is that the universe is essentially a projection analogous to the image on a computer screen, and just as the screen image must be constantly refreshed, so the “image” of our physical universe must be refreshed many thousands of times per second, with changes from one image to the next being effected by the cosmic information processor's calculations. (This idea, by the way, offers a solution to Zeno's “arrow” paradox; the arrow, like an animated cartoon character, is stationary at each moment in time, but the cosmic CPU alters its position from one “frame” to the next, creating the illusion of motion.)