I’ve long believed that the works attributed to William Shakespeare of Stratford were originally written by someone else – someone who had the benefits of more extensive education and life experiences. For quite a while I subscribed to the Oxfordian theory – namely that Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, was the true author. This was mainly because of many apparent parallels between incidents and figures in de Vere’s life and episodes and characters in the plays. But for various reasons I’m no longer sold on Oxford as the Bard.

Not long ago I took a look at two alternative theories – one positing Christopher Marlowe as the author and another nominating Francis Bacon. The Baconian theory is the oldest of the three and the least popular one today. Still, if you wade through the 740 pages of The Bacon Shakespeare Question, by N.B. Cockburn, you may find yourself nodding in appreciation of the author’s arguments more often than you expected. As for Marlowe, the idea is that his official death at Deptford in 1593 was faked for political reasons (he was an espionage agent working for the government), after which he went into exile and wrote the plays, using the Stratford man as a front. Ros Barber wrote an enthralling novel based on this premise, The Marlowe Papers, written from Marlowe’s point of view, entirely in Elizabethan-style blank verse. (This may sound like slow going, but it’s actually a page-turner.) I also read A.D. Wraight’s nonfiction books on the subject, such as The Story that the Sonnets Tell, and checked out a Marlowe website.

And here’s what I discovered: Any one of these stories can be pretty convincing, because each has an internal logic of its own. In every case, at least some possible connections between the authorship candidate and the works of Shakespeare can be identified. Certain of these connections can seem pretty strong. Once these links in the chain have been forged, the rest of the narrative can be filled in around them, with the publication dates of the plays and other details shifted to fit the candidate’s life. Like the unwary guests who used the bed offered by Procrustus, the life of Shakespeare can be forced to fit a preconceived pattern.

The result? Cognitive dissonance and intellectual mystification. If you read a good Baconian tract, you’ll feel convinced that Bacon is your man. Read up on Kit Marlowe, and suddenly you’re a Marlovian. Remind yourself of the case for Oxford, and Oxford it is! But all these things cannot be true at once, unless you opt for the highly dubious theory of “group authorship,” in which every candidate had a hand in producing the works. And art-by-committee doesn’t seem like a satisfactory answer.

In other words, you arrive at a dead end. And when this happens, it’s probably best to revisit the route that took you there. Some mistake was made, probably when you were just starting out.

I’ve come to think the mistake is a pretty simple one. If you start looking for the man (or woman) behind the Shakespearean corpus by examining different well-known figures from the Elizabethan era, you’re bound to light on enough similarities to suggest you may be on the right track. Because the Shakespearean works are so large, so broadly open to multiple interpretations, and so packed with incidents and personalities, almost anyone can be picked out as a candidate for authorship. This is true even of less popular candidates like Henry Neville, William Stanley, and Thomas Sackville. Every one of them has at least some features in his biography or extent writings that could conceivably point to a secret identity as Shakespeare.

In other words, those who’ve been hunting for the true Shakespeare have started off on the wrong foot. What this approach has accomplished is to provide us with an ever-increasing list of candidates, each of whom has points in favor and points against, with no way ever to resolve the issue.

What’s needed is a different, more objective approach. And although it’s still controversial, I think this approach has, in fact, been discovered. The discoverer in question is Dennis McCarthy, who, in collaboration with his colleagues June Schlueter and Michael Blanding, has used vast computerized databases of English literature to find specific, sometimes word-for-word parallels between passages in Shakespeare and the writings of his contemporaries. The upshot of his research: Sir Thomas North, the acclaimed translator of Plutarch’s Lives, wrote the early court plays that were later adapted for the public stage and attributed to William Shakespeare.

The search for parallels is nothing new; people have been doing it for over a hundred years. Baconians, for instance, claim to have discovered more than 1600 parallels between the writings of Bacon and the works of Shakespeare. But as Dennis McCarthy points out, nearly all of these parallels involve only one or two words or commonplace expressions and truisms. The same is true of parallels between the extant writings attributed to Oxford and the Shakespearean corpus. In the case of Marlowe, there are a few more specific parallels, including cases where Shakespeare is obviously pointing to Marlowe or even quoting him directly, but even here, the number is not large.

By contrast, McCarthy’s method has yielded thousands of specific parallels not found between any other two writers. And some of those parallels involve text strings as long as six or seven words. This may not sound like a big deal. I admit that it didn’t sound terribly convincing to me at first. The only way to wrap your head around how rare it is to find a parallel like this is to try it yourself.

I’ve done that, though only in a few cases. I picked some of the word-for-word parallels listed in McCarthy’s book Thomas North: The Original Author of Shakespeare’s Plays and entered them in Google as well as, sometimes, Google Books. (I could not use the more sophisticated EEBO database that McCarthy generally employs, because I lack the necessary academic credentials.)

Admittedly, Google and even Google Books are not ideal because, when the terms are surrounded by quotation marks, the search engine will find only passages that are spelled the same way. And spelling in Elizabethan or Jacobian literature is highly erratic. So there is a fair chance that some parallels will be overlooked. (The EEBO results do include variant spellings.) But the purpose of my tests was not to confirm that these passages are unique to Shakespeare and North, but rather to show how rare they are in general. I picked text strings that did not sound wildly unlikely; before I started, I had trouble believing that I would not get multiple results from non-Shakespearean and non-Northian sources.

First I searched for a line from Cymbeline: “an office of the gods.” Nothing but Shakespeare turned up.

I tried “if it be thy chance.” Beside Shakespeare and North, the only hit from the relevant time period was a French “romance” called Astrea, Part One, which was “translated by a person of quality” in 1657, well after the publication of the First Folio.

Next: “openly known to the world.” Again, there were no other hits from the relevant centuries, except a 1690 legal case in the colony of Virginia.

Then: “man is so very a fool.” Only Shakespeare showed up in the right time period. Even North’s use of this passage did not appear, because it apparently is not part of the Google database.

Then: “both in blood and life.” I really thought this one would score more hits, but it didn’t.

The same holds true for “praise her for her virtues.”

And for “love I bear your grace.”

I concede that just reading these examples, as you’re doing right now, is not entirely convincing. The mind has a tendency to assume that there simply must be more instances of such seemingly common phrases, or that it’s a fluke, or that other, similar text strings would get more results. The only way to make the scarcity of these (or other) phrases real to yourself is to run your own searches. It doesn’t take much time, and you’ve got to see it to believe it.

The case for North as the author of the original versions of Shakespeare’s plays is not limited to database searches, but that’s where it begins, and that’s what provides it with its initial power. We’re not picking North just because some aspects of his life have a possible connection to Shakespeare; we’re picking him because, as McCarthy writes:

North and Shakespeare do not just share a few unique verbal parallels but thousands—thousands of lines and phrases that occur nowhere else in any other known text in the English language. And these linguistic matches do not come from just a few chapters in Plutarch’s Lives; they are found in every chapter in the book—and in every section of The Dial of Princes, The Moral Philosophy of Doni, and Nepos’ Lives. [These are all books that North translated.]

The case for North goes further, however. McCarthy continues:

And, most significantly, they come from personal writings that North never published— and that Shakespeare would have no reasonable way of obtaining and no rational reason for trying to assimilate into a play. The playwright has even based entire scenes out of North’s journal entries and constructed plays out of North’s marginal notes.

Space does not permit an in-depth examination of the latter claims, but you can find it in McCarthy’s book, his website, or his Substack. What is most significant is that a search of the North family’s personal library has yielded books that were almost certainly used in the planning of Shakespearean plays. It’s not just that the books were in the library, but that they were underlined and annotated by someone in the North family, and these page markings correspond precisely to specific details in the plays. Numerous verbal parallels with Cymbeline are found in the markups of a single history volume; included is North’s marginal misspelling of a historical figure’s name; the same misspelling appears in Cymbeline … and nowhere else in literature.

And as suggested in McCarthy’s quote above, North’s private travel journal very obviously served as a source for both The Winter’s Tale and Henry VIII. The parallels with the former play are particularly clear-cut. The travel journal also includes the source of the “play within a play” in Hamlet, right down to the names of the characters – which North got wrong in his journal and which “Shakespeare” got wrong in exactly the same way in Hamlet.

What we’re seeing here is a new way of approaching the authorship question, one which, I think, offers an escape from a labyrinth of irreconcilable theories. We’re not basing North’s candidacy on his personality or the events of his life or anecdotes about him – although, of course, an effort can be made to connect such details with the Shakespearean materials. But that effort is secondary. The theory itself is based on solid statistical evidence and leads to predictions – for instance, that the North family library would contain documents strikingly relevant to Shakespeare – which have been confirmed. Using this theory, McCarthy and his colleagues have been able to track down no fewer than six sources for Shakespearean writings that had never been discovered before.

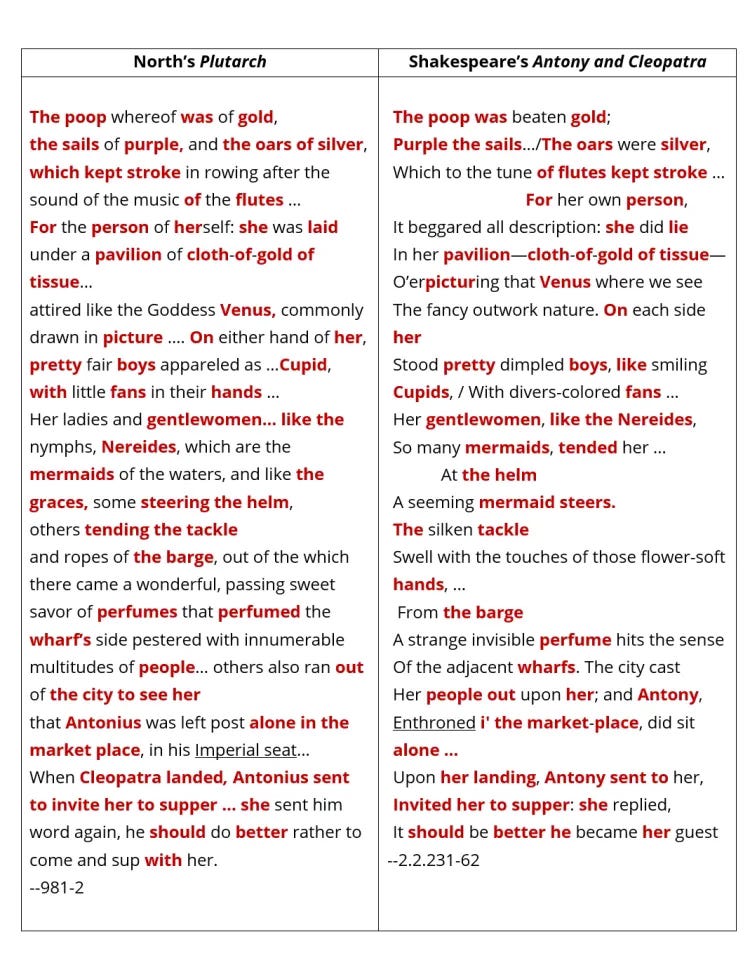

It should be noted that Shakespeare’s debt to North has long been partially understood. Scholars have known for some time that extensive passages in Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, Coriolanus, and Timon of Athens were adapted from North’s translation of Plutarch with minimal changes. These include some of the best-known passages in the plays, such as the description of Cleopatra’s barge:

The plays make use of other sources, to be sure, but no writer other than North is mined for long dramatic passages reproduced almost verbatim. As I said, this much was known. What McCarthy brings to the table is proof that the Northian influence goes far beyond the obvious borrowings in these particular plays. As he writes without exaggeration, “These examples of North’s idiolect throughout the Shakespeare canon represent the most substantial collection of unique verbal fingerprints ever gathered in support of author identification.”

The Northian theory doesn’t resolve all questions. Actually, that may be one of its strengths: It doth not protest too much. There are details about the secret history of Shakespeare’s works that we will probably never know. Other issues are still to be worked out, such as the implications of the theory for both the Sonnets and Shakespeare’s two long narrative poems, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. The dating of the original plays, the circumstances under which they were written, the way in which they came into William Shakespeare of Stratford’s hands, and how (and by whom) they were revised and abridged – all this remains uncertain, though intelligent speculation is possible.

So there is more to do. But I do think this is the way forward. We can argue interminably about this or that nobleman, this or that court playwright or poet, this or that pamphleteer or scholar, and, like Procrustes, ruthlessly stretch and squash Shakespeare’s bibliography to fit the pattern of their lives. But unless we find another writer whose language infuses and permeates the Shakespearean corpus, I think doughty old Sir Thomas is our man.

Maybe. But it requires one to wilfully ignore the obvious in favour of maybes to back up conspiracy theories. The idea that Oxford, North or Marlowe just happened to have written a play years before that fitted the weather was an incredible stroke of luck for their executors. It was topical, as was the Strachey report.

When death is no impediment to writing plays anyone can be proposed as the author. Clearly North was a major source but just as clearly not the author of the later plays.