Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn't there!

He wasn't there again today,

I wish, I wish he'd go away!— William Hughes Mearns

In a previous post I talked about the new Northian theory of Shakespearean authorship – that Sir Thomas North wrote the original court plays later adapted for the public stage and attributed to William Shakespeare. The theory originated with Dennis McCarthy and has been further developed with the help of his colleagues June Schlueter and Michael Blanding.

For reasons I explained earlier, I find this the most compelling explanation of the authorship mystery. It’s the only one backed by hundreds (at least) of unique textual parallels between the Shakespearean corpus and the author candidate’s works. It’s also the only one that’s led to important new discoveries pertaining to the circumstances under which Shakespeare’s plays were written.

So it’s all good, right? Intellectually, I have to say yes. But emotionally, I admit to feeling a bit of a letdown.

Why? Because learning that North was probably the “real” Shakespeare leaves us with something of a vacancy … and a slightly hollow feeling on my part.

Here’s what I mean.

One of the big problems with William Shakespeare himself as the authorship candidate is the paucity of information about him. We do know something – though not much – about his business affairs and legal entanglements. We know when he was baptized and when he died. We know a little about the circumstances of his marriage to an older woman, and we know the names of his children and what became of them. But that’s about it.

We have little sense of his personality, other than as an acquisitive fellow quick to sue anybody who owed him money. We don’t have a decent picture of him; the only two portraits definitely identified as his are the incompetent Droeshout engraving in the First Folio and the disappointing (and possibly altered) bust in the Stratford Monument. He is largely a cipher, a fact that has allowed Stratfordians to fill in the blanks with any number of traits and scenarios that suit their purpose: he was a genius who excelled at school, he was quick-witted and lively, he served as a schoolmaster in the country, he served as a law clerk, he went to war, he toured Europe in a nobleman’s entourage, he was a playboy, he was a scamp, etc.

The many inadequacies of Shakespeare in the role of poet and playwright are what led generations of doubters to search for an alternative. And what alternatives they found! Among many others, there were…

Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. A madcap earl lampooned by his peers as an eccentric clown, cycling in and out of the Queen’s favor, pressured into a marriage with a wife he abandoned for years, imprisoned in the Tower for impregnating one of the Queen’s ladies in waiting, excoriated by his enemies as a “monstrous adversary,” crazy enough to have run through a member of his own household with a sword and to have carried out armed robbery for fun. We have his picture – he looks rather like a fop, though that was the style at the time. We have some of his letters. We have anecdotes about him. He does not come across as either admirable or likable, unless you spin very hard, but he is certainly a larger-than-life personality.

Sir Francis Bacon. An altogether different sort of man – a constant striver disappointed in his hopes for public office throughout most of his life, only to enjoy a meteoric rise in his later years and then an even more meteoric fall into utter disgrace. A polymath who famously stated, “I have taken all knowledge to be my province,” and who made good on his boast by writing a summary of all the scientific knowledge of his day, explaining where it was most in need of correction, and offering methodologies for doing so. We have many of his letters, many portraits, many anecdotes. Like Oxford, he does not necessarily come across well – he profited off the patronage of the Earl of Essex for years, then turned on him and prosecuted him for treason, earning widespread contempt as a false friend – but he is definitely a real person.

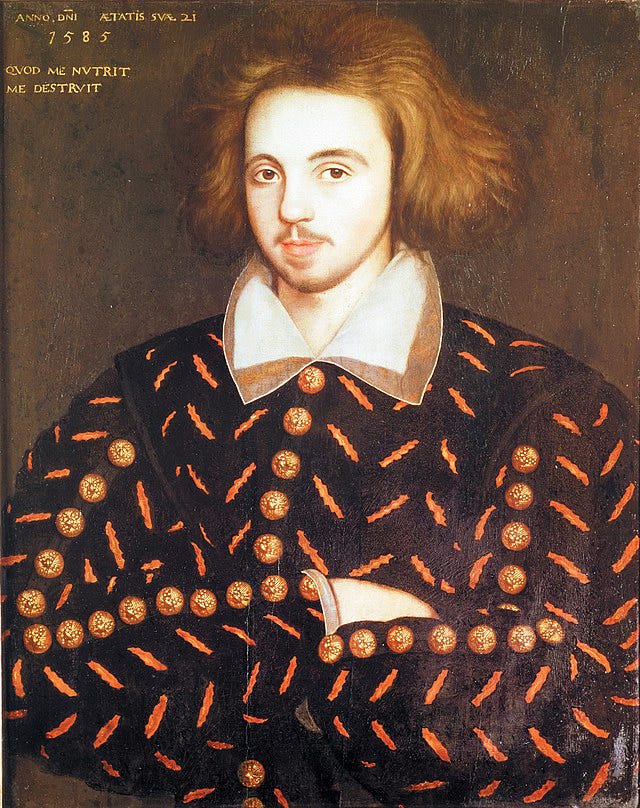

Christopher Marlowe. Marlovians believe that Marlowe’s famous death in Deptford in 1593 was faked, in order to save him from the less-than-tender mercies of the Star Chamber (and to prevent him from spilling the beans, under torture, about his powerful friends and their “atheistic” leanings). Having cheated death, Marlowe went abroad under an alias and continued writing, using Shakespeare as a front man; the first of his pseudonymous works was Venus and Adonis, which they take to be a precursor of Marlowe’s unfinished Hero and Leander. In his short life (or at least the part of his life that preceded “the reckoning” at Deptford), Marlowe established himself as a ferociously quickwitted, sometimes violent, recklessly heretical freethinker. He was an innovator who took the London stage by storm, a controversialist lovingly mocked by pamphleteers, and – best of all – a spy! As a college student, he enrolled in Lord Burghley’s intelligence service to infiltrate the ranks of Catholic recusants plotting against the Protestant Queen. And we have his portrait, or at least a portrait of a Cambridge student generally believed to be him. Of all our candidates, he might be the most colorful, the one Hollywood would want to be Shakespeare.

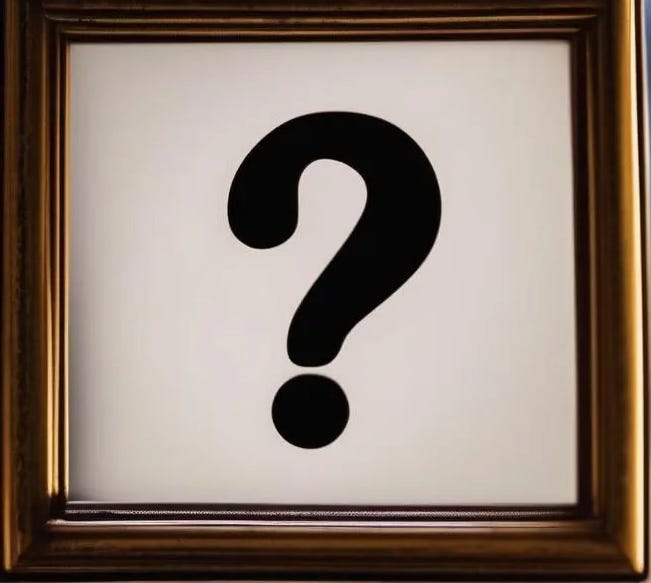

And then there’s North.

A great writer, praised in his own day and ever since as one of the masters of English prose. An industrious translator who produced four books, including the massive two-volume Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. But as Tom Lockwood writes in a good overview of North’s life, as a translator “the manner of his own speaking is muffled, and his identity overlaid, in his literary work.”

What, then, do we really know him?

There are no known portraits of Thomas North. Though we know his date of birth with uncanny accuracy – “born between 9 and 10 o'clock at night on Friday, 28 May 1535,” according to Wikipedia – we don’t know even the year of his death; he simply disappears from historical records after 1603. He was married twice, but we know few details. His first marriage produced two children, dates of birth unknown. He enrolled in Lincoln’s Inn, a law school, on 9 February 1556, but how long he stayed or what degree he earned is unknown. Where he lived afterward is conjectural. There are few, if any, anecdotes about him, and few descriptions, although his great-nephew Dudley North characterized him as “a man of courage, a man learned ... and endued with very good parts otherwise [but lacking] a steadiness comparable to his brother.” (Quoted in Lockwood, cited above.)

We do know the broad outline of his life – raised as a nobleman’s younger son, overshadowed by his older brother, disinherited by his father but maintained for some time by his brother, later apparently estranged from his brother and condemned to poverty, enjoying a measure of comfort in his last years after the Crown awarded him a small sinecure. We know he went to war on two occasions. We know he traveled in Europe at least once – maybe more than once; we can’t say for certain.

But it’s not enough. Who was he, really? What did he look like? How did he behave? We can picture him fat like Falstaff (at least when he was relatively prosperous) or lean like Cassius. We can picture him as merry prankster or sober introvert. We can picture him old before his time or perpetually childlike. We can imagine him as a roué with the ladies or a mostly celibate bookish type or a closeted gay man. We can imagine almost anything, because we know almost nothing. He does not stand before us as a real, distinct, relatable personality. In many ways he is like William Shakespeare of Stratford – a cipher (though a cipher whose literary talents, unlike those attributed to the Stratford man, are amply proven).

Assuming that North actually is the true Bard, we can only hope that an intensive quest for historical documents relating to his life will turn up new information – maybe even a portrait! – that will help fill in a very sketchy picture. For the moment, Sir Thomas occupies the paradoxical position of being both the best candidate for Shakespearean authorship … and the man who wasn’t there.

Advocates of candidates who were dead by 1605 have to do a lot of inventive back-peddling to have written the later plays. Once we're onboard with the idea of a hidden author, we'd have to expect him to have outlived Will Shaxper and to have been involved with the creation of the First Folio. There's no reason to keep Oxford or North's name secret by 1623, it would have been a great Ta-da!! moment and improved sales.

For a start we should reasonably expect the author to have been at the debut performances of his plays: the 1592 visit by Count Mompeliard is mocked in The Merry Wives, a joke shared in letters by the Queen and Lord Burghley; the 1601 visit by the Duke of Orsino saw Twelfth Night open with him as a character (a wow moment as he appeared on stage infront of himself as Orsino, perfect for Twelfth Night celebrations where everything was turned on its head!). The play includes a ribbing for the puritan Sir Edward Knollys and his attempt to woo Mary Fitton. The 1600 embassy of the Moroccan prince, Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud, is cited as the inspiration for Othello; King James I's opening speech to Parliament colours Measure for Measure; Hamlet echoes Lord Burghley's aphorisms; The Tempest, despite Oxfordian claims, is absolutely tied to 1611, following on from a year of the most torrential weather Europe has ever experienced on record and clearly inspired by the Strachey report.

So we know from 1592 until at least 1611 the author was intimately involved at the courts of Elizabeth I and James I, any other timelines are, quite frankly, ridiculous. He was closely connected to the Earl of Southampton, Robert Cecil, John Shirley of the Middle Temple and his sons and the Herbert brothers.

Someone rewrote and enlarged the text of Othello when it was printed in Quarto in 1622, a year before First Folio, was our hidden author still alive? Collating and amending texts for his life's work?

North's notated works are a huge discovery in Shakespeare studies and will no doubt illuminate new discoveries, but was he the great Shakespeare? I very much doubt it.